People

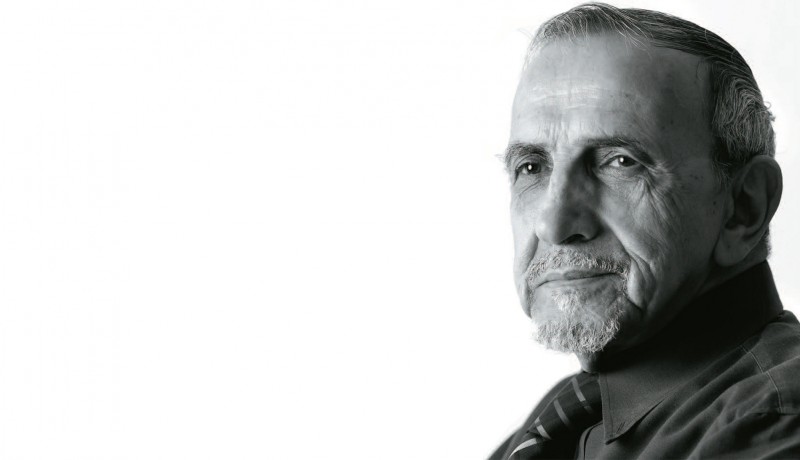

Thirty years after retiring from the National School of Drama, 82 year-old Ebrahim Alkazi remains active in the artistic sphere. Jai Arjun Singh in conversation with the veteran of Indian theatre

So what is it you’d like to know about my dreary life?” asks Ebrahim Alkazi, twinkle firmly in eye. This is high irony, and he probably knows it; you’d be hard pressed to find a life more dynamic than the one lived by this veteran of Indian theatre. From the 1950s through to the 1970s, initially in Bombay and later in Delhi, Alkazi was a flag-bearer of the theatrical tradition, a director who brought new realism and purpose to Indian drama, a teacher who nurtured some of the great talents of the era. And though he retired from the National School of Drama (NSD) 30 years ago, he has remained active in the artistic sphere — collecting and documenting old photographs and paintings, conceptualising and curating exhibitions.

Currently, it is an exhibition of old photographs of Lucknow, from the time of the 1857 Mutiny. The exhibition has moved from Delhi to Mumbai and will go to Lucknow in September. “We try to reach as wide a public as possible,” he says, going into his office and emerging with an elegantly produced book, Lucknow, City of Illusions, edited by Dr Rosie Llewellyn-Jones. Flipping the pages, he explains each photograph, the camera angles — and in the process, giving you an idea of the unerring visual sense that made him such an influential theatre director. “I developed a visual approach to the theatre,” he often says, “as opposed to just a literary approach. I was very concerned with how the stage would look, and with the overall design.”

Though he walks with a barely noticeable stoop, there’s little else to suggest that Alkazi is 82. Dressed in a sharp suit, he still comes to his office, the Art Heritage Gallery in the Triveni Kala Sangam basement, at 11 am every day after spending an hour at the Alkazi Foundation in Delhi’s Greater Kailash. His steady, clipped voice could easily belong to a man 25 years younger and he rarely pauses for breath. There’s a natural storytelling talent on view when he talks about his life; he has an impressive memory for specifics and his descriptions are vivid. As theatre director Bansi Kaul, one of his students in the 1970s, says, “When Alkazi described a performance, we could imagine it unfolding. He was a charismatic teacher.”

Given his sense of discipline and structure, it isn’t surprising that Alkazi prefers to tell his story chronologically, rather than have a free-flowing chat. He was born to Arab parents in Pune and schooled at St Vincent, a Jesuit school, and those early years played a major part in his development. “The Jesuits had a comprehensive view of education,” he explains. “They picked up our talents and encouraged us to hone them. The principal, Father Rifkin, was in charge of the library and he knew exactly what every student was reading.”

At home, his father, a Bombay-based businessman, was a liberal and young Ebrahim had exposure to books and magazines from around the world. He fondly recollects reading the Cairo-based magazine Rouz-al-Yusuf, to which the great writer Naguib Mahfouz (later a Nobel Laureate) would contribute. “I hardly had a holiday in my early life,” he says, “never an idle moment. After school a tutor from Saudi Arabia taught us Arabic.” He speaks with some pride of the communal living that he was accustomed to as a youngster. “In our community there was no master-servant relationship,” he says. “Everyone ate together and the help were given a share in the family businesses. I have treasured these values of equality all my life.”

It was at St Xavier’s College in Bombay in the 1940s that Alkazi took his first strides in theatre. According to him, Sultan Padamsee, his friend and later brother-in-law, was a director on the scale of Orson Welles. “He started the Theatre Group, but died tragically young and a great deal of responsibility fell on my shoulders.” Alkazi flung himself into acting and directing, and subsequently spent three years at the Royal Academy of Theatre in England, which gave him plenty of exposure to the possibilities of theatre. “But I wanted to come back and work in India.” He did, and founded the Theatre Unit in Bombay.

“I wasn’t interested in plays that had been successful on Broadway or the West End,” he says. “Instead I wanted to encourage Indian playwrights and deal with subjects that were relevant to the Indian scenario. In fact, Alyque Padamsee and I fell out over this issue.” Alkazi has always been very focused and clear about what he wanted. Kirti Jain, another of his students and a former director of the NSD herself, concurs that he was a director who “needed to make the decisions”, to be in charge of all aspects of the production.

Bombay was a vibrant place in the 1950s. Alkazi speaks of spending time with M F Husain, Tyeb Mehta and Usha Amin; Mulk Raj Anand who founded Marg, a magazine for the arts; and Raja Rao, who wanted to set up a Parisian café in Bombay. He recalls working at the terrace theatre of the Bhulabhai Desai Institute, and later renting a fifth-floor flat for Rs 150 a month near Breach Candy Hospital and setting up a theatre: “The audience would enthusiastically walk up six flights of stairs to see a play!” Simultaneously he became interested in collecting art — at one point he even managed to get together 47 original ceramic works by Picasso.

A turning point occurred in the early 1960s when the chairman of the Sangeet Natak Akademi asked him to come to Delhi to help set up a national drama school. “I’d always wanted to do plays by Hindi writers, and this was my chance.” However, in 1962 Delhi was an unsettling place — to Alkazi, it felt like a village compared to Bombay. “It was a peculiar, retarded, feudal world,” he exclaims, talking in particular about the southern parts of the city. “Kailash Colony, where we set up our base in a shabby building owned by tent-wallah, was so far out that no taxi would go there.” Chuckling, he recounts one of his earliest experiences in the city: seeing two men hoisting a dead donkey on a scooter by the side of the road. “This was my introduction to Delhi. It was surreal, like something out of a Luis Bunuel film!”

The flip side was that he realised Delhi’s ancient monuments would be fantastic sites for theatre. “There was a space behind the tent-wallah’s house, we picked up stones and built a makeshift stage there, lined with cow dung and with a thatched roof. We played to full houses.” Later they would move to a more sophisticated venue — the Rabindra Bhavan building near Mandi Chowk — but those early days were heady. Alkazi began reading a lot of Hindi literature and plays. He was especially taken by Mohan Rakesh’s Ashad ka Ek Din, based on the life of Kalidas, and Andha Yug, a drama set in the aftermath of the Mahabharata War. “I was told these were radio scripts, not real plays, but I was convinced they would work with the right direction.” He would have reason to feel vindicated later on when both plays were prescribed for a BA course.

The breakthrough came one evening at the Ferozshah Kotla stadium, where he got permission to stage Andha Yug. “Pandit Nehru came to watch it, and diplomats and huge crowds followed him.” It was a successful performance, though one that ended with the prime minister gravely warning Alkazi to watch out for snakes when he staged his productions near monuments!

What would he say was his greatest strength as a director? “My intellectual humility,” he replies, referring to his constant desire to add to his knowledge. Alkazi’s son Faisal, himself a theatre director and educationist, adds that his father has always strived for perfection. “There has been a professional stamp to everything he has done,” says Faisal. “And he always taught us to work without cutting corners.”

Alkazi’s liberal background and interest in a number of different forms also helped. While the NSD under his supervision primarily represented Indian theatre, it was also open to traditions from other countries — for instance, he once got a Japanese director to stage a production in the classical Noh tradition. “We designed the stage in the style of the Noh,” he says, showing us an old photograph. “The form is not very different from Kathakali, and we were able to explore that connection.”

One reminiscence quickly follows another as Alkazi discusses his productions — including translations of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House and Shakespeare’s Othello — and his bouts with critics; once, after a reviewer likened an actress’s performance to a “cackling hen”, Alkazi wrote a letter to then editor of The Times of India Sham Lal, saying the critic’s writing was “like the cackling of a hen no cock would look at twice”. The letter was published in its entirety.

Not that he doesn’t criticise his actors. “Actors tend to get conceited very soon,” he says. “It’s important to know how to keep them balanced.” There were some performers, he says, who were brilliant but too low-key for the theatre — like Pankaj Kapur. “His talent really came out on the big screen.” It’s common to find theatre persons who are resentful or dismissive of cinema, but Alkazi is pragmatic. “I think movies are important and have always encouraged film appreciation.”

A mildly cantankerous side emerges when we discuss corporate sponsorship for theatre. “It’s a beautiful, velvet glove,” he says. “They pick up popular actors and thematic plays and often do a good job within a certain sphere. But would it be possible to get sponsorship for a hard-hitting play that’s critical of the media, for instance?” As for the hefty sums of money doing the rounds on the art scene (a subject close to his heart), he says, “There’s a whole lot of colossal rubbish being produced and sold in the name of art. And when it comes to good work that sells well, most of the money doesn’t even go to the artist.”

We’ve been talking for a while and he asks if we’d like to have coffee. “I take lots of sugar,” he says jovially, hardly the thing you expect to hear from someone his age. This is my cue to ask him how he stays so fit. “I eat very little,” he says. “Besides, when you have a strong passion for your work, the energy comes naturally. I consider myself fortunate to have spent my life doing things I enjoy.”

Importantly, he wears his erudition lightly. “He was extremely well-read, a walking library,” says director Vijay Kashyap, who worked with him on productions like Tughlaq and Razia Sultan, “and yet he never used high-flowing words. He explained everything in very simple language.” But as Alkazi himself is fond of saying, “The thing to know is that you don’t know enough.” He follows this philosophy tirelessly; much of his time is still spent reading, researching, learning new things about his areas of interest.

After retiring from the NSD in 1977, much of his work has been in art — as collector, gallerist and curator. Having lived in Kuwait, London and New York at various times in the past couple of decades, he has built up a sizeable collection of 19th century photographs. His wife Roshen Alkazi has run the Art Heritage Gallery for over 40 years, but hasn’t been well lately. Ask him more and Alkazi shows reticence. “She would inspect every painting,” he says, deflecting the subject, “and I felt it was necessary for me to be involved too.” He is also measured when talking about his children: Faisal has done a lot of work with handicapped youngsters, he says, and daughter Amal Allana is chairperson of NSD. “She is a director of great originality,” Alkazi says. Was he a hard act for his children to follow? “In any artistic field, it tends to be difficult for the second generation,” concedes Faisal. “But it wasn’t bad because I became a director after he retired, so there weren’t too many comparisons.”

The meeting with Alkazi ends on a nostalgic note as he shows us a collection of photographs from his theatre ventures. There are shots of elegant set designs into which he invested so much effort. Rehearsals with actors, including a young Om Puri wearing a Japanese mask. A long shot of the Purana Qila, where Alkazi discovered that Nehru was right: there were indeed snakes around! When he first went to the site, he recalls being told that he couldn’t use the ground because it was sacred. “It’s already being used as a public lavatory!” he retorted. “I’m only cleaning it up.”

I sense he wouldn’t run out of anecdotes to relate, even if we spent several more hours talking. But he’s the picture of courtesy, inviting us to visit him at home and hear more stories. “Do you want me to powder my nose?” he asks while posing for the photographer, a theatre professional to the last.

Photo: Idris Ahmed Archival courtesy: NSD Featured in Harmony – Celebrate Age Magazine May 2007

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….