People

Rebuilding ancient fortresses is not a job for the faint-hearted. Fortunately, Aman Nath, the foremost restorer of vintage properties in India, is an intrepid visionary, writes Natasha Rego

There are many places in India that possess a certain time-travelling magic, but only few allow you to wake up in these alluring locations. Step into the grounds of the 17th-century Deo Bagh in Gwalior, the 19th-century Ramgarh Bungalows in Nainital, or the 20th-century Piramal Haveli in Shekhavati, and take a deep breath. You will be transported back in time, even as you enjoy a supply of sun-dried towels to soak your face in, a bed lined with crisp linen, and other modest luxuries of modern-day life.

It’s hard to imagine that, until a few years ago, these heritage hotels were in various states of ruin, with no paths leading up to them, let alone running water and electricity.

What, or rather who, brought about this transformation? Professionally, he’s an author, historian and art curator. He’s also been called a philosopher, fakir and ascetic. He’s certainly a sharp dresser! But above all, he is a visionary. We speak of Aman Nath, founder of the Neemrana group of ‘nonhotel’ hotels, who’s in the business of converting ruined fortresses, daunting bungalows and old havelis into “rose petals and smiles”.

“We were absolutely privileged—even spoilt—in the past, to dream up a structure and, lo, it was built! However, India has no tradition of archives. This is one of the shortcomings of an otherwise alive civilisation,” Nath rues. But having spent over 32 years rebuilding, resuscitating and revitalising India’s heritage, it has become second nature to him. If you keep your senses awake and alert, he says, history’s built heritage is the best teacher.

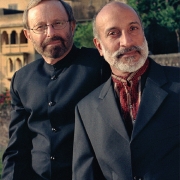

He first set his sights on the enormous ruins of Neemrana Fort as a 27 year-old. He was driving back from the Shekhavati region of Rajasthan with his late partner Francis Wacziarg, when they came upon a magnificent sight: the dilapidated 15th-century fort on the Aravalli foothills that lay ignored since its time.

“The locals looked at my black beard and thought I was a smuggler. Nobody could understand why I would be interested in the ruins. But people are sensitive. When you deal with them, employ, empower and look after them, they look after you,” says Nath, who has since restored 32 unlisted historical sites, both sprawling and small, along with Wacziarg, in 18 states across the country.

Now, he’s working on his grandest project yet: 15 years in the making, the unfinished and abandoned palace in Tijara is nothing short of a labour of madness. Spread over eight precarious acres, Tijara has 75 rooms that are open to visitors, while a few more are still in the works.

It’s a story out of a history book… dynamite being used to cut through the rocks, donkeys that transport material up an unpaved path, and locals being employed to care for the palace as their own. “We do one room at a time and we do it lovingly,” he says.

Nath speaks to us over the phone on a September afternoon from his New Delhi office in Lajpat Nagar. “This place is the antithesis of everything I do. It’s a slim, modern, functional office in our own building. There are books and tables, and a bit of a mess.” The destination offices around the country are for the weekends. But WhatsApp keeps him linked to each property for details of construction, repair, art, systems controls and management. “I work for 18-20 fascinating hours a day, scribbling notes and making sketches on little pads. We also have a fabulous young team that won’t let me age beyond 25!” says the 67 year-old.

At the office, the fan mail never stops. Guests send praises for Neemrana’s brand of experiential tourism and members of erstwhile royal families inform him about the ruins in their possession that could afford a revamp. Nath reads them all. As we speak, he receives one, purportedly from a royal family that belonged to a southern state.

All these words of praise and encouragement are a constant reminder that there is so much to do and so little time. “I just wish I had the pocket to do it all,” he laughs.

EXCERPTS FROM AN INTERVIEW

What triggered your fascination with historical monuments?

My parents were refugees from Lahore, so there was no physical, ancestral caress. But I grew up in Nizamuddin, right by a Mughal gate that led into Humayun’s Tomb, while listening to fairytales of a lost child who saw light in a castle on the hill and was asked in by a princess. Don’t we all grow up and try to fill the vacuums we felt as children? As kids, we would also visit amazing sites like Tughlaqabad, Red Fort, Hauz Khas, the Old Fort. When I read history at college, all this dovetailed quite naturally into action.

Tell us about the first time you and Francis Wacziarg laid eyes on Neemrana Fort. What went into restoring it?

The year was 1977 when Francis and I were driving back from Shekhavati. The afternoon sun lit the lime plaster of the ruined Neemrana Fort, which showed up in a special orange-gold. I turned left onto an unmarked road, drove up about halfway, and parked by a handsome police station. Kids ran with us as we passed a camel or two on our way up. The entrance to the fort was viciously spiked to guard against elephant attack. Partially open, it looked like a giant and ominous alligator. I walked in, willing to be swallowed by my own cosmic destiny.

In 1986, I acquired it with my friends O P Jain and Lekha Poddar. The scale of madness that came upon us was enormous—the volume and diversity of headaches were never ending, as were the costs of organising staff and supplies, pumping water to different levels and supplying diesel for the gensets that ran full time. It took us five years to complete the first phase. We finally opened for guests in 1991. Later, Francis and I bought OP and Lekha out.

How do you go about the restoration process?

Neemrana works on unlisted heritage buildings where the end use can be changed. For instance, a 700 year-old fort like Kesroli in Rajasthan doesn’t have to be readied again for medieval warfare. Round holes in the ramparts, which were used as toilets by sturdy soldiers, would be a laugh for plump urban clients who can hardly squat on their haunches. Some of them would have to be lifted up by crane. Ha!

On a serious note, our work is to make old structures ready for modern habitation, with some resemblance to contemporary lifestyles within. Friends of Neemrana understand simplicity over fuss; we don’t need Italian marble or a Jacuzzi to lure or impress our clients. In fact, those who have been through enough in life want to move from bling to khadi, from more to less. What we can give you, though, is green mango curry on a rustic rampart or homemade strawberry ice-cream under a peach tree in the Kumaon.

How do you find and employ skilled experts of various disciplines involved in the restoration processes?

Back in 1984, when I began restoring the first haveli in Sohna, Haryana, it was easy to find masons who worked in lime mortar. One thought they won’t last. But India is an amazing repository of skill and of jugaad, the most ingenious makeshift technology that provides inventive solutions.

At the Neemrana properties, the greatest compliment is to our living traditions, which live on in the veins of our craftspersons and masons. No one can tell the old from the new. We build organically on a need-based system, much as it was done in the past. For instance, if stables needed to be built, more hills would be cut up in such a way that they would fit right into place, like they were always there.

How do you incorporate the comforts of the present—air-conditioning, lighting, plumbing—within the regal ambience of these ancient monuments?

This is a challenge that we got into headlong and began to enjoy more and more. We had once joked with some American guests about our special technology where the electricity, ventilation and water were supplied without wires, ducts and pipes. They believed it till we started laughing! Actually there are two aspects to this: the functional and the aesthetic. You want the air-conditioning to work but don’t want to see the cables and gensets. If, however, guests did see our plumbing and sewage plans, they would admire us even more.

Once a property has been restored to its former glory, what does upkeep and maintenance involve?

When a 15th-century property has been restored and revitalised, it is naturally much better, more liveable and visually more beautiful than it was without attached bathrooms, air-conditioning, gauze doors to catch the breeze without the insects, and more. In the past centuries, the water at Neemrana Fort was brought up in large copper cauldrons on donkey-back, so naturally they couldn’t plant hanging gardens on terraces cut into the hill. We married the raw beauty of the fort walls with modern facilities and design sensibilities. An American designer once commented that it was very Alhambra-like, but the difference was that one could also live and wake up in it now.

The hotel business is a rather flaky one. How did you come by a working model?

When I called our properties ‘non-hotel’ hotels, Francis was surprised. My friend Aroon Purie [editor-in-chief] of India Today even phoned and said, “Why begin with a negative?” I had to explain that Neemrana, as a fortress, was originally designed to keep people out; we were trying to transform that forbidding shield. It was certainly not built as a hotel with rooms along corridors, so the nomenclature was chosen to avoid false notions of hospitality and service. We still don’t have room service or televisions in the rooms. Our clientele would appreciate that, we had hoped, and it worked! But the world has markedly changed in one generation; so, too, the necessities. To not have Internet today is to disconnect patients from their oxygen!

This is undoubtedly a story you have told numerous times… but who was Francis Wacziarg?

Francis was a fabulous person—a lost Western soul who found his cosmic connect in India. He was a business graduate from Paris who saw his share of socialist rebellion in the Paris of 1968. He read Aurobindo and Krishnamurti but did not fall in the guru trap to be lost among the ‘baba cool’ youth of that time. He was terribly restless to try out things even if they didn’t work. He had no regrets, though he would say that if we had met earlier, he would have gained time. When his term as the head of BNP in New Delhi had ended and they wanted to send him to Nairobi as a bank manager, he felt he had connected with his past life in Tamil Nadu (!) and stayed on. Above all, he wanted to dabble in the arts. He would say to me, “I am an artist without an art.” When he left us, much too early in 2014, it was less true. He had learnt that life itself was an art. It was great to walk this path together.

How has it changed since his passing?

Francis joined Neemrana when it had already opened, and once we put our energies together, we wasted little time. We did about 30 properties in 32 years, though some were just follies or love at first sight that made no business sense. But not doing something can never live up to the joy of doing something passionately. The brand hasn’t changed even though we run fewer properties now.

It’s been more than 30 years since you rebuilt Neemrana Fort. What have the biggest learnings been through the years?

However modestly one looks back, it is daunting to think that what took five centuries to build can still be added to with the same vision—in just three decades. Even though it can be a huge nuisance to work in a field where the babus think you will run away with India’s heritage, this country remains among the few places where one can still attempt whatever one dreams. For me, it has never been about possessing heritage; we are at best ‘custodians’ of our heritage—not owners. When one is sensitive in the idioms of traditional construction, one can build intuitively in India with great success, because the medieval and modern coexist in the ever-flowing eternity that India is.

How do you decide which property you want to work on?

As intuitively as one falls in love, I guess. You must trust your deepest instincts. You can’t wake up in each ruin to know how splendid a winter sunrise can be. So I actually have a heightened sense of simulation within spaces to do an imaginary walk-through—and magic is easily recognisable!

What is your latest project?

I have been obsessing over Tijara Fort-Palace in Alwar since I first saw it in the 1980s. It’s been most challenging … almost as undoable for us as the 13 other hotel groups who had collected the tender papers but had not dared to bid. I can only imagine what its builder must have conceived, as there were no blueprints. But many clues of a great mystery lie close at hand. I had conceived an entrance gate and when we cleared the hill, some 10 ft below appeared the wall I had wanted to build! An invisible contour map guides me and I don’t need to do scale drawings to imagine how it will end up looking.

Why is it important for us to look at our past and preserve our heritage?

Because our present can only stand proudly on a past that is preserved with contextual dignity. Otherwise, future generations will float in a rootless vacuum. It is our heritage that gives India a part of the gravitas that it holds internationally.

Given the neglect of our historical monuments, do you think Indians are not heritage-proud?

The mindset is changing—but it hasn’t yet changed. Earlier governments just thought it was enough for them to ‘own’ India’s heritage, irrespective of whether they had the funds or expertise to do something constructive with it. The private sector or individuals like us were considered interlopers. Now, this Government wants to push the PPP model. But how much controversy was whipped up over Dalmia Bharat taking the responsibility of Red Fort! We go one step forward and two backwards.

What are the most amazing architectural developments of ancient India you have come across?

The town planning of Indus Valley as well as all the collective wisdom that went into making the oldest university of the world, Nalanda, in 800 BC. But nothing can beat Ellora! To think that 400,000 tonne of stone was hand-chipped over 800 years to carve out a monolithic Shiva temple from a volcanic mountain… it defies the imagination even today.

What has modern Indian architecture retained from the wisdom of the past?

Alas, very little. In school, we were still fascinated with foreigners, even had a complex about them. By the time I was an adult, India had begun to assert its identity in art, design and architecture. Later—and one wonders how—we went back into this cycle of lacking confidence. First Scandinavian, then Singaporean design and architecture became role models and India got off track. Traditional Indian architecture has more to teach us besides just lending its derivative and cosmetic frills.

What is your daily routine like?

I have always risen early. My metabolism, however, urban as it is, has always moved with the planets. I am sure that we are all connected, but if you must drug yourself with whiskies and vodkas, why would you be surprised if both the moon and sun drown like ice and lemon to blank out the cosmic links we are born with, and force us to live by lamp light!

Has age affected your life?

Not yet… but you can’t stop people’s perceptions. Feet-touching and too much show of social reverence irritate me. Early on I told my staff in Rajasthan who would all too naturally bend to touch my feet that I would reciprocate with the same gesture. Soon the dignified ‘namaste’ was restored. Now, despite my white beard, the younger lot inform me of my ‘young’ presence and ask why I don’t tire like them. However, there are things I don’t want to do anymore, like travel long miles to dine with famous people!

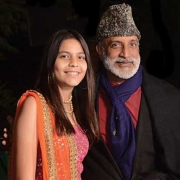

Fatherhood came late in life to you….

I had considered making my own progeny with at least two admirable women but that was not to be. Finally, I was gifted a daughter, Aadya, by a mountain family that loved and adopted me. I used to joke with friends that I got the profit of the wedding without the loss! Fatherhood came naturally, as being a grandfather also eventually does strike everyone as normal without having borne the children.

Do you get to pick and choose where you’d like to lodge your writing desk?

I have had many study tables in many homes. I have worked a lot in Ramgarh, Kumaon; the Himalayan foothills bring out the best in the brain. I moved my books on Indian mythology and spirituality there, as also the difficult, slow reading ones. I wrote four to five books there, on a large English desk I had bought from a retired army man. But now I can sit anywhere and write: on the floor, the bed, the dining table. I think it’s your head that needs to be arranged, not the aesthetic of the quill and inkwell.

Tell us about your work on Section 377. What motivated you to join Sunil Mehra, Navtej Singh Johar, Ritu Dalmia and Ayesha Kapur to file a joint petition in the Supreme Court?

I am not the red flag sort but so much needs doing and updating in India that we should all naturally become a part of it. Our nation and its majority religion are perhaps the most open—hundreds of thousands of devotees go to worship at Sabarimalai, where Shiva and Vishnu (as Mohini) made love to produce a baby. In India, [former prime minister] Vajpayeeji could be a bachelor-father without the press bringing his private life into a belittling Lewinsky affair. So when I was asked by friends to sign a petition in which I believe, I did it with full conviction. That Section 377 has now been repealed is a tribute to India returning to its open, pre-colonial morality. The love of mankind will finally be legal in India!

ROYAL RETREATS

OLDEST

The 14th-century Hill Fort-Kesroli (Alwar, Rajasthan)

MOST INTRIGUING

… is perhaps an underground step-well I built with three friends in Haryana; it has yet to go public

MOST FUN

Our Rajasthan properties are the most playful where guests often lose themselves

MOST CHALLENGING

Both the flagship 15th-century Neemrana Fort-Palace (Neemrana, Rajasthan) and the 19th-century Tijara (Alwar, Rajasthan) have been mammoth challenges

MOST COVETED

Different seasons have different demands; some love the intimacy of the 19th-century Ramgarh Bungalows (Nainital, Uttarakhand) or the in-house heritage of the 17th-century Deo Bagh (Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh)

FAVOURITE

Always the one that I am working, or reworking, on

- ANUPAM SAH

- C SEKAR

- DINESH DESHPANDE

- INDRA VIJAY SINGH

- MOHAMMAD IMTIAZ & REYAZ

- SAILAJA PATURI

- SANDEEP KATARI

- SHASHIKANT MAYEKAR

Photos courtesy: Aman Nath Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine October 2018

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….