People

Sai Prabha Kamath in a rare conversation with India’s foremost technocrat Dr Raghunath A Mashelkar, who believes it is the power of ideas—not the size of the budget—that fuels innovation

It’s not often you get to meet one of the greatest scientists and nation-builders of our times. Thus, the task of interviewing India’s foremost technocrat Dr Raghunath Anant Mashelkar was admittedly daunting. Not to mention that researching this multifarious personality turned out to be a never-ending exercise!

A good omen, however, was the date of our interview, 27 July—the first death anniversary of legendary scientist-former president Dr A P J Abdul Kalam—making our meeting extra special. Dressed impeccably in a dark blue suit, Dr Mashelkar receives us warmly in his spotless and sophisticated office on Pune’s Baner Road, unmindful of our early arrival. And as we begin to understand the man behind the scientist, a shloka from the Ramayana comes to mind: Janani Janma-bhoomischa Swargadapi Gariyasi (Mother and motherland are superior to heaven).

Over the years, the 73 year-old’s life and career have reflected this belief. Brought up by his poor, widowed mother, he strived to fulfil her wish—of scaling great peaks in education. In 2010, in her memory, he instituted the annual Anjani Mashelkar Inclusive Innovation Award under the aegis of the International Longevity Centre-India (ILC-I) (of which he is president), in an effort to fuel ultra low-cost solutions for the poor and elderly.

Indeed, since the 1970s, his work has dovetailed with the government’s efforts in nation-building and he has played a crucial role in shaping the country’s science and technology policies. As chairman of the National Innovation Foundation and Reliance Innovation Council, he is deeply involved with India’s innovation movement and has been promoting the concept of Gandhian engineering—getting ‘more from less for more’—around the world. As president of Global Research Alliance, an organisation with 60,000 scientists across the world, he scripted the $ 55-million Vietnam Inclusive Innovation project and, as a result, has become the global ambassador for ‘inclusive innovation’ that meets the needs of people with a low income. What’s more, for over two decades, Dr Mashelkar has been propagating a balanced intellectual property rights regime and has spearheaded the successful challenge to the US patent on Basmati rice as well as the use of turmeric for healing wounds.

Little wonder then, that 35 institutions, including the universities of London, Salford, Pretoria, Wisconsin, Swinburne and Delhi, have conferred honorary doctorates on him. And his pioneering work has won him accolades aplenty including the S S Bhatnagar Prize (1982), Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru Technology Award (1991), JRD Tata Corporate Leadership Award (1998), the Padma Shri (1991), the Padma Bhushan (2000), Material Scientist of the Year Award (2000), Star of Asia Award (2005), President of Indian National Science Academy (2004-06) and the Padma Vibhushan (2014).

Never one to rest on past laurels, Dr Mashelkar—nicknamed Ramesh—powers ahead. Often referred to as a ‘dangerous optimist’ for his positive vision for India, he is very active on social networking service Twitter. “I am a great believer in spreading good news and have great fun on my Twitter handle,” he says. Pointing to his tweets in memory of Dr Kalam, he says, “The entire nation misses him. Today, while paying respects to the People’s President, I have recalled my memories with him.”

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW

A bright young boy with a humble beginning… please share your journey.

I was six when my father passed away and my mother, with me in tow, moved from our native village Mashel to Mumbai to make a living. She did odd jobs to make ends meet; even two square meals a day was a struggle for us. Until I was 12, I walked barefoot and studied under the streetlights. I went to Union High School, a Marathi medium municipal school in Girgaum. It was supposed to be the poor school for the poor but the teachers were rich in values and ideologies. Despite being one of the toppers in the SSC Board Examination, I considered quitting studies as my mother didn’t have the means to afford higher education. Our friends collected ₹ 200 to get me admission in Jai Hind College. Subsequently, I could continue my education due to a scholarship granted by the Sir Dorab Tata Trust. It is rather paradoxical that I still go to Bombay House—where I used to go every month and collect the ₹ 60 scholarship amount—as I am on the board of directors of Tata Motors and chairman of their CSR committee. Life has truly come full circle.

Who were your inspirations and mentors? What were the turning points?

My first inspiration is my mother, an unlettered woman herself, who goaded me to achieve more in studies. My second inspiration is my science teacher Principal Bhave from Union High School who ignited the passion for science in me and gave me the philosophy of life, ‘Focus and you can achieve anything’. My first turning point was meeting my guru Prof Manmohan Sharma under whom I completed my PhD within three years. I have imbibed a lot of values from him. Ours is a unique combination of guru and shishya—both of us are FRS [Fellows of the Royal Society]. Another turning point was meeting my mentor Bharat Ratna Prof C N R Rao later in my life. He has the ability to set very high goals and spot young talent. Even today, at 83, he has the energy of an 18 year-old; he gets up at 4.30 am every day and by 8.30 am, he is in the laboratory. He still produces 40-50 research papers a year. Meeting this amazing person had a deep impact on my life. He gave me the important lesson of climbing up a limitless ladder of excellence. He has received all awards in science except the Nobel Prize and hopefully he will receive it sooner than later.

Following a degree and doctorate in chemical engineering (from the University of Bombay), you had a cosy job in the UK. What made you return to India?

That was an important career decision I made in 1974 when I returned to India from the UK, where I was well-settled. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had sent Director General of CSIR Dr Y Nayudamma to get the best and the brightest minds from India settled around the world, and offer them jobs on the spot, cutting red tape. Dr Nayudamma painted such a picture about the future of India and the need for young scientists in nation-building that within half an hour of meeting him, I decided to head back home. The fact that there were many more attractive offers from other countries didn’t matter at that time because I always think from my heart.

What has been the most memorable moment of your life?

When I received the FRS, in London, in 1998. I signed in the same book where Newton had signed. I was thrilled to discover Newton’s signature on page 9! For a boy who walked barefoot till 12, it was a moment of great pride.

You have coined the term ‘Gandhian engineering’—innovating in a way different from standard practice. How significant is it for the world today?

Mahatma Gandhi said, “The world has enough for everyone’s need, but not for everyone’s greed.” When you have an exhaustible resource, it is our duty to conserve it for future generations. Reflecting upon this Gandhian philosophy, in 2008, I created the mantra ‘Gandhian engineering’ to get ‘more from less for more’. We would always do less from less. If one can afford a scooter, we try and give him a better scooter for the same price. But Ratan Tata set out to make a car for the same price without compromising on quality. This way, we are getting more from less for more [people]. This is affordable excellence. Even the poor have aspirations—they have the right to enjoy the same quality at an affordable price. However, this requires a completely different strategy. In 2010, C K Prahalad, one of the greatest thought leaders, and I wrote what later turned out to be a breakthrough paper, “Innovation’s Holy Grail”, for Harvard Business Review that showed how exactly we can achieve that. The incredible idea of ‘more from less for more’ has now caught the attention of the world; in fact, the World Economic Forum held a session on it only six months after we published our paper. The basic concept of Gandhian engineering—creating products and services with quality, sustainability and affordability—has come to centre-stage now.

Are you happy with India’s progress in science and technology?

In spite of being a resource-constrained country, India has done well in science. Indians may not have won many Nobel Prizes in science—but that cannot be the only benchmark. I am happy to see young minds turning to science; the quality of our research is going up and our presence is being felt in the world of science. In technology, too, we have done well in terms of affordable excellence. We have done a Mars mission for just $ 74 million, whereas the US did it for $ 671 million. When we were denied the cryogenic engine and supercomputer by other nations, we came up with our own versions without anybody’s help. Through our indigenous Chandrayaan-1, we were the first to discover water on the moon’s surface. I am happy that we have accomplished these milestones with limited resources and a low-cost Indian budget.

Indeed, we are seeing reverse brain drain in India now….

Earlier, Indian scientists, academicians and researchers looking for greener pastures turned to other countries. But the scenario is changing and India is becoming a land of opportunities. As industrial enterprises are seriously getting into research and innovation, there is great demand for scientists here. Around 1,000 leading foreign companies have set up their research and development centres in places such as Bengaluru, Chennai, Pune, Gurgaon and Hyderabad, and around 2 lakh scientists and technologists are working with them. With our institutions expanding rapidly—30 new central universities, several new IITs and IIITs—graduates from top schools like Berkeley, MIT and Cambridge are accepting faculty positions in India. Today, more and more high-quality young scientists are returning home as our facilities are as good as other countries and technological advancement is on a par with the world. In fact, India has become a global research and development platform, something I had predicted in 1995 in my Thapar Memorial Lecture, which was presided over by none other than Dr Manmohan Singh. But people refused to believe me then and called me a ‘dangerous optimist’. Twenty years later, that dream has come true!

Have there been limitations to research and development in the country?

Yes, only our mindset. We have been satisfied with being first to India. But we have to dream of being first to the world. We have to open new windows of knowledge ourselves. When we do the first, we are followers. When we do the second, we become leaders. Breakthroughs should take place in our country. When people complain about lack of resources in the country for research and development, I give them the example of a young scientist, Konstantein Novoselov in his mid-30s from Russia who made the revolutionary discovery of graphene [considered a wonder material in electronics with the potential to transform the future] using just scotch tape and flakes of carbon graphite. The groundbreaking experiment led him to share a Nobel Prize in Physics with Andre Geim, in 2010. Hence, it is the power of the ideas that matter, not size of the budget. In fact, one can see more innovation in adversity.

As president of ILC-I, what made you institute the Anjani Mashelkar Inclusive Innovation Award, named after your late mother?

Though my mother faced many a hardship, she led a life of courage and dignity, and motivated me to scale great heights in academics. I instituted the award honouring her last wish—of using science to help the disadvantaged and poor elderly. Through the award, we endeavour to promote inclusive innovation rooted in Gandhian engineering.

Our ultimate goal is making high tech work for the poor. Solutions should be extremely affordable—not just low-cost, but ultra low-cost. That is the true meaning of inclusive innovation—not just the ‘best practice’ but the ‘next practice’.

You chair the expert panel of the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan. What is your roadmap for a clean India? Is it a distant dream?

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has, indeed, set a challenging target by 2019. I chair the 19-member committee that will leverage technology to improve sanitation and the availability of potable water in India. We are building close to 50,000 toilets per day, ahead of our target, except the fact that it is uneven in different states. I believe the bigger challenge is in creating social awakening in using toilets. However, I appreciate our prime minister for his courage and conviction in starting this campaign that has become a mass movement. I hope we live up to his expectations.

What is your secret to success?

Work, work and work. I get up at 4.30 am and don’t go to bed before 11.30 pm. Five hours of sleep is more than adequate for me.

What are your other interests?

I don’t go to bed without listening to classical Indian music, though I don’t understand its nuances. I find it soothing and relaxing. I have an amazing collection of technical books and biographies—from celebrities and politicians to sportsmen and leaders. I am more interested in reading about the process in which personalities developed.

I believe your wife Vaishali was your student before marriage….

[Smiles] Yes, my wife Vaishali is the sister of my close friend. I was tasked with giving her tuitions in subjects where she was weak, and I fell in love with her. She is a wonderful human being and has played an incredible role in my life. Also, she is a fabulous artist and has held exhibitions of her paintings in Pune and Mumbai. With my 24×7 work schedule, she has brought up our children, Shruti, Shubhra and Amey, admirably.

What do they do?

My daughter Shruti has done her master’s in communication studies from Pune University and is a homemaker. My second daughter Shubhra is a lawyer in the US. My son Amey is with GenNext Ventures—he leads the accelerator for start-ups, trying to contribute his own bit to our prime minister’s mission of ‘Start-up India’!

Do you think technology has made lives easier for silvers?

Certainly. Today, I find many elders quite at ease with their smartphones. Messaging services such as WhatsApp and Skype and social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter are helping them beat loneliness. With lifestyle apps, silvers are finding it easier to keep a tab on their health and fitness too.

While keeping themselves busy, how can silvers become change agents?

Your biological age doesn’t matter—you are as old as you think you are. At 93, Sir G I Taylor wrote a single-author paper on the stability of the soap bubble. Hildebrand wrote about diffusion in structured solids when he was celebrating his 100th birthday. Each one is capable of contributing to society in their own way. Keep going till your last moment.

MILESTONES

1982: S S Bhatnagar Prize

1991: Padma Shri

1995-2006: Director General, Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi; enunciated “CSIR 2001: Vision & Strategy”

1998: Fellow, Royal Society (FRS), London

2000: Padma Bhushan

2003: Medal of Engineering Excellence by World Federation of Engineering Organisations, Paris

2004-06: President of Indian National Science Academy

2005: The first Asian scientist to receive the Business Week (USA) Stars of Asia Award

2010: Wrote “Innovation’s Holy Grail”, a path-breaking paper, along with C K Prahalad for Harvard Business Review

2011: Released the book, Reinventing India

2014: Padma Vibhushan

Oct 2016: To receive his 36th honorary doctorate from Monash University, Australia

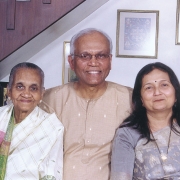

Archival photo courtesy: Dr R A Mashelkar Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine October 2016

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….